Connecticut’s prison population is the lowest its been in 27 years — much of that recent shrinkage the result of concern for the safety of inmates and prison employees amid the ongoing novel coronavirus health emergency.

Today there are 1,385 fewer people behind bars than there were on March 1, the beginnings of the COVID-19 crisis. On April 29, the prison population fell to 11,062, the lowest it has been since the beginning of 1993.

Newly released data gives insight into how the pandemic has affected several aspects of Connecticut’s criminal justice system. Thursday, Marc Pelka, Gov. Ned Lamont’s undersecretary of criminal justice policy and planning, gave members of the Criminal Justice Policy Advisory Committee a presentation on the new figures. Here are five takeaways from that report.

1. Arrests dropped between February and March 2020, unlike the same period in previous years.

Statewide arrests in March 2020 were 11% lower than March 2019. Typically, there’s an uptick in the number of arrests between February and March, but this year they fell by 7%.

“We know that arrests are the main feeder into the criminal justice system,” said Pelka.

Overall pretrial admissions to jails and prisons fell sharply, as well. The decline became more significant after each successive week in March, which Pelka said underscored the impact of social distancing and closures of businesses across the state.

“I think also you see the impacts of the necessary changes in court operations, responding safely to the public health emergency,” Pelka said.

“Even with the month of March only having half of the month being impacted by the COVID-19 response and crisis, that was the fewest pretrial admits that we’ve ever seen on record since we’ve been collecting that data from the DOC, back in 2008” said Kyle Baudoin, lead planning analyst of the Criminal Justice Policy Planning Division. “And April is going to be far, far lower than that, given the entire month will have the response in place.”

Pelka suggested that the drop in pretrial admissions freed up staff to focus on preparing people for release from correctional institutions so they could have a successful transition to their homes.

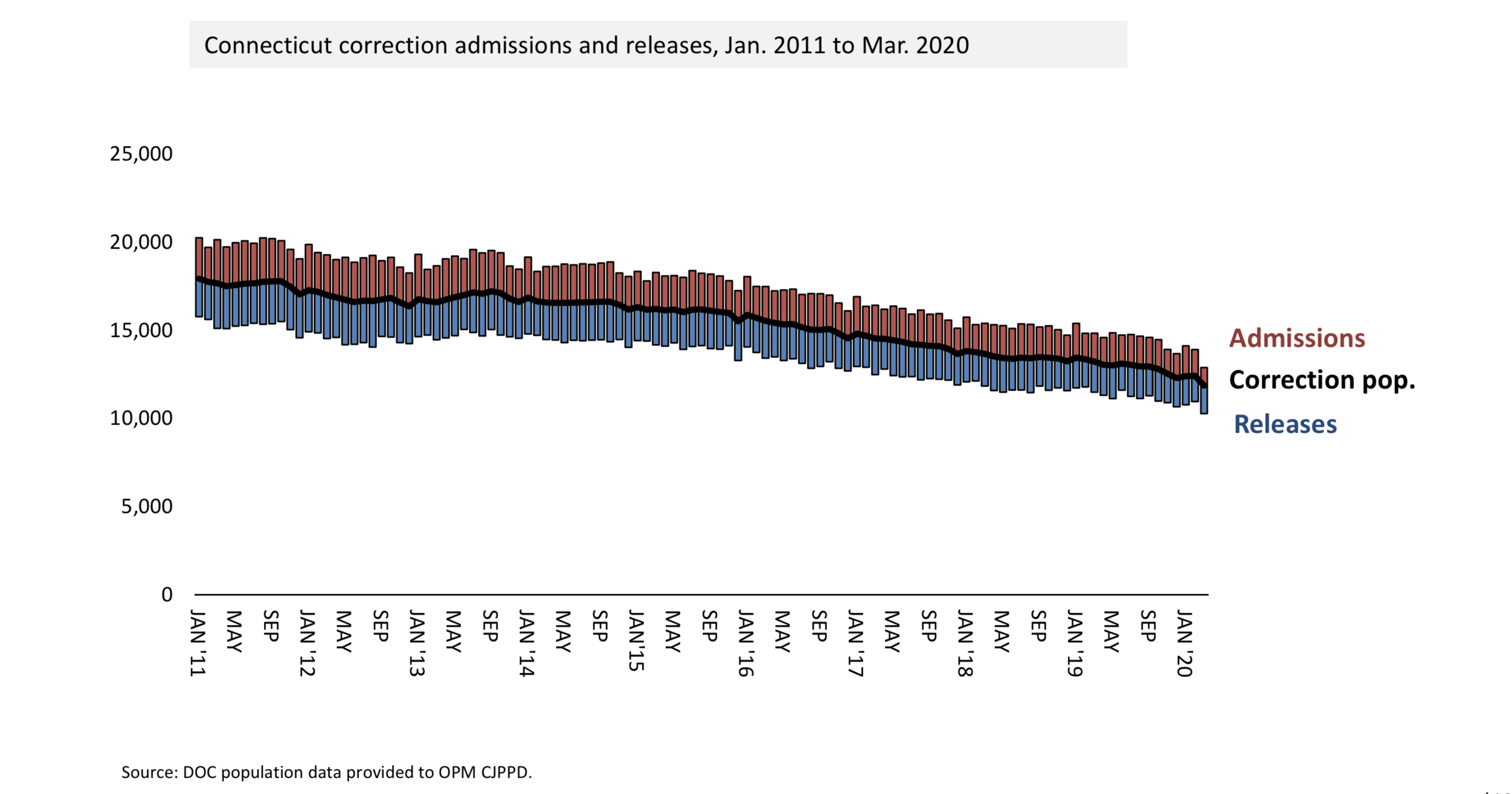

2. The incarcerated population dropped throughout March because admissions fell and releases increased.

March’s drop in prison population wasn’t just because of reductions of people entering the system. More than 750 people were let out of correctional facilities — 237 of whom were at the end of their sentence. In March 2019, 730 people were released from DOC prisons or jails.

This past March saw a marked increase in the number of people released under the DOC’s discretion. More than 520 people were released to some form of community supervision prior to the end of their sentence. That was almost three-fourths of the month’s releases. Around 300 people were granted discretionary release the previous month, compared to 411 discretionary releases in March 2019.

“Discretionary release is important because it provides a period of supervision and access to community programs for people who have been incarcerated,” Pelka said. “The alternative outcome is a negative one. It’s ‘end of sentence,’ under which the DOC is legally required to release someone after their court-stipulated sentence, and there is no supervision and limited access to programs.”

The increase in discretionary releases between March 2019 and March 2020 was larger for black and Hispanic people than the total population. The release of black inmates increased 52% between the two months. Discretionary releases of Hispanic inmates increased by 40%. Release of white inmates increased 5%.

3. There was still a racial disparity in discretionary releases in March 2020.

White inmates accounted for 199 of the 522 discretionary releases in March 2020 –38% of those released to some form of community supervision before the end of their sentence. That’s notable because white people make up less than 30% of the total incarcerated population. Black people accounted for 37% of discretionary releases, despite making up around 43% of those in custody. Almost 24% of those released under the DOC’s discretion were Hispanic. They make up around 27% of the total prison population.

To qualify for discretionary release, a prison inmate must have a housing plan approved by the DOC. Melvin Medina, public policy and advocacy for the American Civil Liberties Union of Connecticut, said the racial disparities in discretionary releases reflect existing inequities in community supports.

“If you prioritize an existing home plan, you’re talking about black and Latino people who have more complicated housing relationships. What sounds like a race-neutral policy actually isn’t because the negative impact of it exacerbates existing disparities,” Medina said. “It’s not enough to identify who has a housing plan; the state needs to take the next step and offer a housing solution.”

4. Housing support funds helped 28 people, with more money on the way.

The Office of Policy Management allocated $148,500 to house people who would otherwise be released from prison to homelessness. The funds can be used for security deposits, short-term rent subsidies or interim housing in hotels.

“This is an effort to provide a rapid rehousing,” said Pelka.

Each month, the DOC releases to homelessness around 60 people who have reached the end of their sentence. The housing funds are meant to identify and secure short-term housing assistance, so those released from prison or jail don’t have to rely on community resources already spread thin by the virus.

Richard Cho, CEO of the Connecticut Coalition to End Homelessness, said in the last 30 days the DOC has referred 61 people to his organization who could benefit from the funding. Of those, 17 people have been housed and are receiving rental assistance. Eleven people are in hotels or motels, 10 have been placed in transitional housing. Four people either refused assistance or were unable to be contacted.

“It is my hope that we can continue to expand upon this so we can serve folks who are going to be released beyond the next 30 days,” said Cho.

Pelka said the federal CARES Act has established funding streams that states can use to support justice-impacted residents in search of housing, though it is unclear when that money will become available.

5. The number of people held pretrial on bond has fallen since March 1, with a larger reduction for those on lower bonds.

5. The number of people held pretrial on bond has fallen since March 1, with a larger reduction for those on lower bonds.

The Department of Correction, the Judicial Branch, prosecutors and public defenders have spent a lot of time over the past month working to reduce Connecticut’s pretrial population, to ensure no one is detained because they can’t afford to post bond.

Chief Public Defender Christine Rapillo said judges, prosecutors and defense attorneys worked to reach an agreement so people held pretrial could be released in a “planful and individualized way” that wouldn’t compromise public safety.

Gary Roberge, the executive director of the Court Support Services Division, said officials began working on cases where defendants were accused of more minor crimes, and then worked their way up. They started working on cases where people were held on technical violations of probation, then cases where individuals were held on lower bonds for less serious crimes, and then gradually began examining more serious cases with higher bond amounts. Reductions were common for all bond amounts, with the deepest declines in cases where people were held pretrial on bonds of less than $20,000.

Rapillo said her staff are continuing to review case files “with an eye toward disposition,” and the work is ongoing.

“We’ve been able to get a lot of people home to their families,” she said, “and we continue to work on it.”